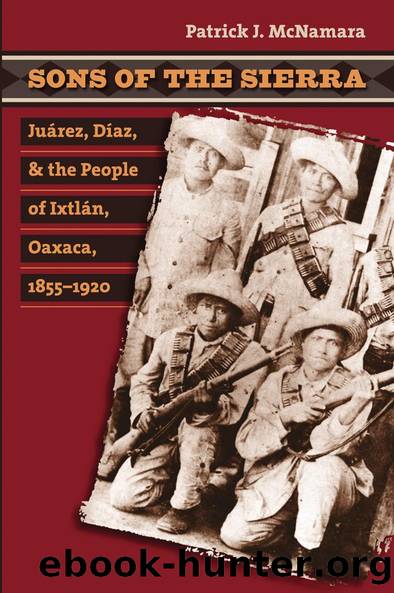

Sons of the Sierra by Patrick J. McNamara

Author:Patrick J. McNamara [McNamara, Patrick J.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780807857878

Barnesnoble:

Publisher: The University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2007-02-26T00:00:00+00:00

Conflicts with Capital

As with conflicts between villages, confrontations with capitalist industries grew after 1890. The irony, of course, is that Oaxacaâs rural economy was expanding rather than contracting. Increased competition, and not limited deprivation, led to greater unrest in Ixtlán district. The dozens of gold and silver mines scattered throughout the district and the cotton textile factory at XÃa became the immediate targets of peasant discontent.

In 1895 a sudden increase in the international demand for precious metals ignited greater interest in the Oaxacan mining industry. Foreign and Mexican investors looked to the potential of mines in the state, and most observers believed that Oaxaca was Mexicoâs âLand of Tomorrow.â63 In particular, the richest and most promising mining region in the state, the Sierra Zapoteca, became the focus of intense foreign investment. The stateâs largest gold and silver mine, Natividad, finally began earning a profit for shareholders after the 1895 boom. Porfirio DÃaz, for example, received more than five hundred pesos in dividends in the fall of 1898 alone. His old friend Francisco Meijueiro would have been pleased to know that Natividad had finally paid off.64 Still, familiar obstacles to growth continued to hold back more sustained economic expansion for Natividad. The need for new and improved roads throughout the district increased as traffic to and from the mine grew during the boom years, and the call for a railroad spur reaching Natividad became even louder.65

Other complaints surfaced for the first time. In 1900 Manuel Muñoz Gómez complained to President DÃaz that certain factors prevented Oaxaca from reaching its potential in the mining industry. As a newcomer to Oaxaca, Muñoz Gómez wanted to invest in the region, especially in Ixtlán district, but the âprovincialismâ and âignoranceâ of the working people concerned him. Muñoz Gómez thought it would be better to bring in more experienced laborers from northern Mexico.66 But this suggestion would not have impressed DÃaz. Jobs, rather than economic growth and profits, were responsible for maintaining peace and stability in the district. The mining boom may not have produced tremendous wealth for investors, but it guaranteed jobs for the people.

Oaxacan mines ultimately produced only a fraction of the anticipated profits, but the mining industry in Ixtlán district still changed dramatically during the boom years. New owners tried to impose new restrictions on Zapotec laborers, and the workers began for the first time to directly challenge the exploitative labor contracts under which they suffered. From 1879 to 1900, the number of mine claims in Ixtlán district remained relatively constant, ranging from forty-six to forty-one. Most of the mines remained idle, but they belonged to wealthy Oaxacans either living in the district or in Oaxaca City. In 1879 just twelve different families owned all of the mines. Miguel Castro owned twenty-two mines, by far more than any other individual. José Ferrat owned eight mines; Constantino Rickards owned six; and Pedro Meixueiro owned three mines. Together with other wealthy investors, most of the Ixtlán mine owners also held shares in Natividad. By 1900, only modest changes had taken place among the mining elite in the district.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Canada | Caribbean & West Indies |

| Central America | Greenland |

| Mexico | Native American |

| South America | United States |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15380)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14535)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12413)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12106)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12042)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5800)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5458)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5419)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5316)

Paper Towns by Green John(5201)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(5019)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4974)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4511)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4497)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4454)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4403)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4359)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4336)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4209)